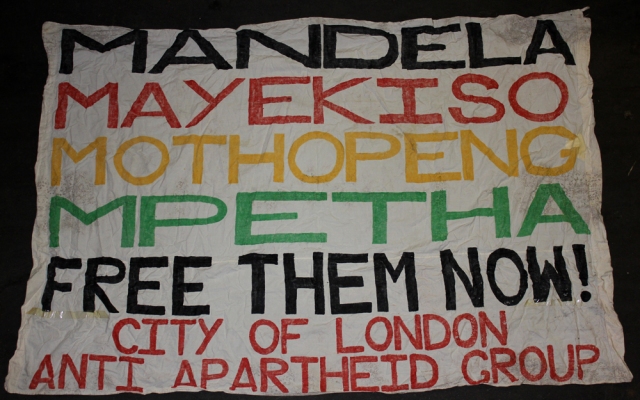

Nelson Mandela’s death has been announced tonight (5 December 2013). Although this news is not unexpected, its impact on people around the world will be significant, not least for those who maintained a four-year protest for his release in central London. In the late 1980s the City of London Anti-Apartheid Group [City Group] kept a constant vigil outside South Africa House in Trafalgar Square calling for the release of Nelson Mandela. The Non-Stop Picket of the South African Embassy became a feature of London’s landscape and an iconic image of global, grassroots opposition to apartheid.

Since July 2011, Gavin Brown and Helen Yaffe from the Geography Department at the University of Leicester have been researching the history of the Non-Stop Picket with funding from the Leverhulme Trust. This article draws on our archival research and interviews with former participants in the Non-Stop Picket, considering the actions they took in support of Nelson Mandela and their reflections on his political legacy.

Anti-apartheid protesters watch from the steps of St. Martin-in-the-fields Church, as others defy the ban on protests outside the South African Embassy, 6 May 1987 (Source: City Group)

The Non-Stop Picket began on 19 April 1986. It kept going, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year until (just after) Nelson Mandela was released from jail in February 1990. The main demand of the Picket was the release of Nelson Mandela, but it was always about more than this. The Picket recognized the symbolic importance of Nelson Mandela as a leader of the struggle against apartheid, it also called for the release of all political prisoners in South Africa and Namibia, for the implementation of full sanctions against South Africa, and the closing of the South African Embassy in London. By calling for the release of all political prisoners and detainees, the Picket recognised that Mandela as a leader could not be separated from the popular movement he represented. It also recognised that that movement was plural. Andy Higginbottom, the Secretary of the City Group at the time, explained,

City Group was for … the release of Nelson Mandela and all political prisoners. The emphasis on ‘all’ is quite important because it was saying “yes, we support the ANC, but also everyone else who is a victim of fighting apartheid”. Probably more important in my view, the framing was not only against apartheid, but against British collaboration with apartheid. (Andy Higginbottom, 17 April 2012)

The proposal to launch a Non-Stop Picket for the release of Nelson Mandela was made by the exiled South African activist Norma Kitson at a meeting of the City Group in early 1986. The group had been regularly picketing the South African Embassy since 1982 and had run an 86-day non-stop picket in August of that year. Building on that experience, it had the organisational capacity to consider the daunting task of committing to maintain a constant presence outside the embassy until Mandela was released. At that time, no one knew how long that would take.

Although international pressure was building in the mid-80s for Mandela’s release, the decision to launch the Non-Stop Picket was not purely based on the case of just one man. Carol Brickley, City Group’s Convenor, explained that the decision to launch the Picket related to wider events in South Africa.

But the value of it was in the doing of it rather than in the end of it. Especially given what was going on in South Africa. I mean, it’s not that you decide that sort of thing in isolation. There was an enormous build up of militancy in the Townships in South Africa from 1985 onwards which was extraordinary and very different from what had gone before. So that was the background to us making any decisions. (Carol Brickley, 21 February 2013)

The launch of the Non-Stop Picket took place in the context of renewed trade union militancy in South Africa, the uprisings in the townships, the launch of the United Democratic Front, and increased military actions by the armed wings of the ANC and other liberation movements.

In calling for Nelson Mandela’s release, the City of London Anti-Apartheid Group always remembered that he had been not just a political leader of the ANC, but centrally involved in its decision to turn to the armed struggle in the early 1960s. Indeed, David Kitson, Norma’s husband, had been one of the four-strong group that took over the high command of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) following the arrest of its leadership at Rivonia in July 1963.

Day and night, the supporters of the Non-Stop Picket stood on the pavement directly in front of the embassy’s gates. Picketers engaged passing members of the public in dialogue, asking them to sign the petition calling for the release of Nelson Mandela. By the time the Non-Stop Picket celebrated its 1000th day on 12 January 1989, over half a million signatures had been collected.

There were other activities and protests too. On 14 March 1987, 5000 people marched six miles across London on the ‘March for Mandela’. The demonstration started at Whittington Park in North London and ended at the Non-Stop Picket of the South African Embassy in Trafalgar Square.

On 6 May 1987, there were parliamentary elections in South Africa. With apartheid still in place, and anti-apartheid leaders like Nelson Mandela still imprisoned, the Black majority were denied a vote in these elections. In response and protest, City Group organised an alternative, just election – an opportunity to ‘vote’ for Mandela. The group produced ‘voting cards’ in the form of a postcard. ‘Voters’ were encouraged to put their name to the demand “I/We call for the immediate release of Nelson Mandela and all South African political prisoners and detainees”, and post their vote back directly to the Picket on the pavement outside the South African Embassy. The Post Office, obligingly, delivered them.

While the national Anti-Apartheid Movement held a large concert at Wembley to mark Nelson Mandela’s 70th birthday on 18 July 1988, the Non-Stop Picket held its own celebration. That Monday evening, several hundred people stayed outside the embassy well into the night and at 4am the following morning Boy George joined a conga line around the embassy. On Mandela’s 71st birthday in 1989, the words “Happy Birthday Mandela” were spray-painted in the black, green and gold colours of the ANC on the wall of the South African Embassy, challenging its legitimacy.

When Nelson Mandela finally walked free from on Sunday 11 February 1990, thousands of people converged in Trafalgar Square to celebrate. After nearly four years of their constant presence outside South Africa House calling for his release, the Non-Stop Picket had captured the imagination of Londoners and become the obvious place to mark that historic occasion. For regular picketers, this was a day of celebration, the culmination of what they had been campaigning for. It provided a genuine sense of victory.

I arrived fairly early in the morning when it was still very quiet. Other City Group people began to arrive, and it started like a typical City Group rally. ANC people were there too and setting up a stage and amplification equipment. They were actually very friendly and appreciated our presence. As more and more young black South Africans arrived, it became more and more an ANC event. “Free Nelson Mandela” and Miriam Makeba records were played through the amplifiers. Speeches were made, by various people, including Tony Benn. … The young South Africans started to sing, and then they were toyi-toying. It was wonderful! I felt as though I was at a real South African celebration, and I was too! The general atmosphere was electrifying … most people were joyful about the great news and full of admiration for what we’d done. (Francis Squire, 27 November 2011)

Yes, it was big. It wasn’t like the picket almost, there were so many people who had gone to Trafalgar Square, including the AAM who had their own platform and were trying to make sure they were the only people who were interviewed. It was exciting. … I felt that City Group had been vindicated. (Carol Brickley, 21 February 2013)

It was amazing. It was a victory, wasn’t it! It was a great justification of what we’d been doing, a great vindication of the activity and campaigning work of City Group, although many people who were not involved and in fact were opposed to the picket, were trying to claim that they had been central to it. In fact the only people who systematically campaigned for Mandela’s release in a militant and newsworthy way in this country was the City of London Anti-Apartheid Group. (David Yaffe, 5 April 2013)

The former non-stop picketers that we have interviewed over the last two years are proud of what they did in the late 1980s. They recognize that their protest played only the smallest part in securing Mandela’s release, but they value the role they played in keeping Mandela and the broader issue of apartheid in the public eye. They celebrate the end of apartheid and the fact that the Black majority in South Africa now have the vote and can participate in democratically determining their future. Nevertheless, many former picketers have expressed disappointment with what the ANC government has achieved since 1994.

I already had my doubts about Mandela, sadly confirmed when he became President in 1994 and helped to turn South Africa into one of the most ideologically neoliberal countries in the world, so impoverishing and dispossessing the South African working class even more than under apartheid. … He was a political prisoner on Robben Island for over 25 years, surviving concentration camp-like conditions, he was a great symbolic, charismatic leader of a dispossessed people. All this only makes the ANC’s betrayal after 1994 and Mandela’s turning a blind eye even more shameful. (Patrick C., 13 January 2013).

Although the release of Nelson Mandela was the headline demand of the Non-Stop Picket, for many who participated in that four-year protest, Mandela was a symbol of something broader. They not only wanted to see an end to apartheid as a human rights abuse, they hoped for the end of apartheid as an economic system based on the exploitation of cheap African labour. Since the end of apartheid, the ANC have promoted a myth that both their resistance to apartheid and the solidarity of the global anti-apartheid movement was always directed towards the kind of negotiated transition that eventually took place in South Africa. The history of the Non-Stop Picket reminds us that many opponents of apartheid hoped for more radical social transformation in South Africa.

Former participants in the Non-Stop Picket celebrate Nelson Mandela’s leadership of the anti-apartheid struggle; recognize his importance as a symbol of resistance during his long imprisonment; but, question his legacy as post-apartheid South Africa’s first President.

For interviews call the University of Leicester Press Office: +44 (0)116 252 2415

Pingback: Nelson Mandela – humanity’s champion | mid-life grooving

Reblogged this on Paulo Jorge Vieira.

Pingback: Non-Stop Against Apartheid in 2013 | Non-Stop Against Apartheid