In June 1984, President PW Botha of South Africa was expected in Britain for talks with Margaret Thatcher. His tour of Europe that summer was intended to promote ‘constructive engagement’ with the apartheid regime (rather than sanctions) and stave of a major political crisis for South Africa. The British Anti-Apartheid Movement planned various protests in response. The City of London Anti-Apartheid Group called a week-long continuous picket of the South African Embassy. As Solomon Hughes explained recently in The Morning Star, security concerns surrounding Botha’s visit drew unwelcome police attention to that and subsequent protests at the embassy.

On 15 May 1984, City Group wrote to Richard Balfe MEP asking him to support their protest against Botha’s visit. They planned a week-long picket of South Africa House from 26 May until 1 June, immediately prior to Botha’s arrival. They announced that this protest had already been sponsored by Tony Benn and Stanley Clinton Davis MPs. Importantly, given City Group’s difficult relationship with the leadership of the ANC in London, the picket was also sponsored by Adelaide Tambo.

As evidence supplied to Solomon Hughes (as a result of a Freedom of Information Act request) reveals, Scotland Yard were well aware of City Group’s plans. They briefed the Foreign Office not only that “the Kitson family plan to stage a vigil outside the Embassy”, but also that,

“The Anti-Apartheid Movement intend staging an occupation of South African Airways office (251 Regent Street SW1) either within the 48 hours immediately before or 48 hours immediately after the visit. They will, obviously, keep their plans secretive so that preventative action cannot be taken, but local police will be alerted and will stand ready to take action to evict the demonstrators if the SA Airways Office require them to do so.” (Letter from [redacted], Security Section, Protocol Department to SAfD, 17 May 1984)

The police advised that, at that stage, the South African Embassy should not be notified of the threat to occupy the Airways offices. A hand-written note in the margins of the letter says “I am worried about 1(b) [the Airways occupation]”. In 1984, City Group was still a local branch of the Anti-Apartheid Movement and it seems very likely, given their later regular occupations of South African Airways, that this too was them. A ‘teleletter’ from the Foreign Office to the British embassy in South Africa (also dated 17 May) confirms that Special Branch obtained this intelligence “from their own sources inside the AAM”. Other correspondence (a letter from the Protocol Department of 11 May 1984) refers to City Group as “a hooligan element” within the AAM. A note from British diplomats in South Africa (10 May 1984) reported that Botha himself “had been somewhat concerned by the hostility of the anti-apartheid lobby in Britain to his visit”.

Just before Botha’s visit to Britain, on 25 May 1984, a volunteer from the national Anti-Apartheid Movement’s office threw paint over the main entrance to the South African Embassy. On 1 June, four members of the National Union of Mineworkers deposited a pile of coal on the embassy’s doorstep in protest at the importation of South African coal in an attempt to break the miners’ strike. Given the heightened security concerns surrounding Botha’s visit, the Metropolitan Police took the opportunity to ban all protests outside the South African embassy with effect from Friday 8 June 1984. A press statement, issued by City Group on 10 June, explained these events:

On 5 June Superintendent Dark of Cannon Row informed our Convenor that the City AA picket scheduled for Friday 8 June, 5.30 – 7.30 p.m. was banned. He claimed that all pickets and demonstrations in the vicinity were being banned due to a banquet for Reagan, Thatcher & Co being held the same evening at the National Portrait Gallery. Bu the evening of 5 June, following protests by MPs, councilors and others, permission was given for a picket in Duncannon Street – near the National Portrait Gallery – but not outside South Africa House. On Thursday 7 June, despite consistent misinformation, spread by Scotland Yard to the Press, it became clear that what was at issue was a permanent ban on City AA’s pickets and not concern for the Reagan/Thatcher banquet. The City Group convenor and Richard Balfe MEP met Commander Howlett on 7 June. […]

Commander Howlett informed us that this was his decision based on his own personal interpretation of the Vienna Convention catering for the peace and dignity of embassies. In his opinion any picket or demonstration outside any embassy would be in breach of the Vienna Convention. He admitted to having consulted no-one in arriving at this decision.

The press release continues by explaining City Group’s response to the ban:

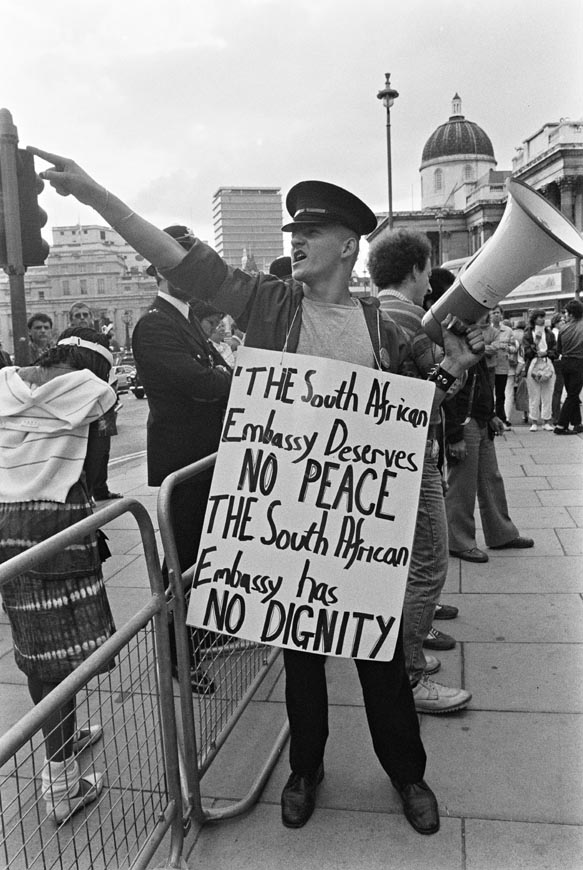

City AA was prepared to resist this attack. On 8 June over 200 people representing a wide range of organisations assembled at Duncannon Street. Among the demonstrators were Ernie Roberts MP, Jeremy Corbyn MP, Rodney Bickerstaffe of NUPE, and Peter Hain.

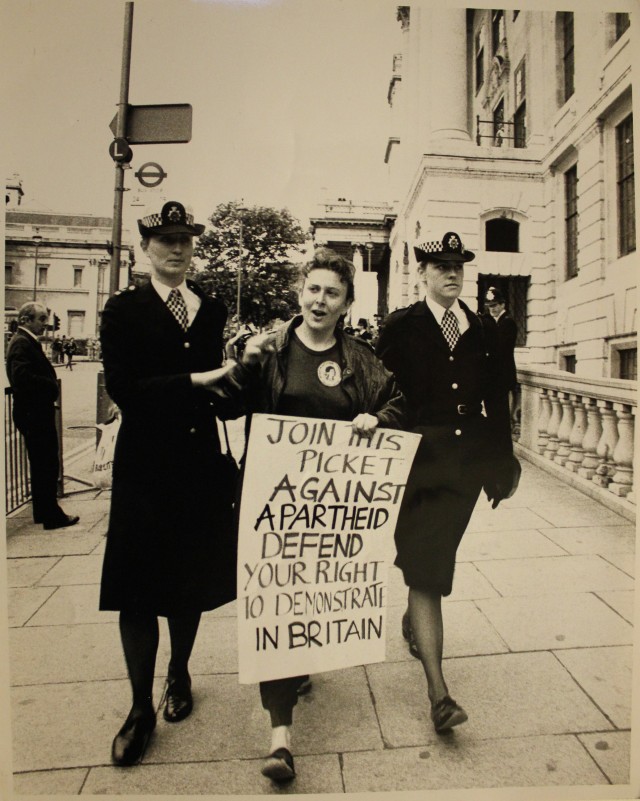

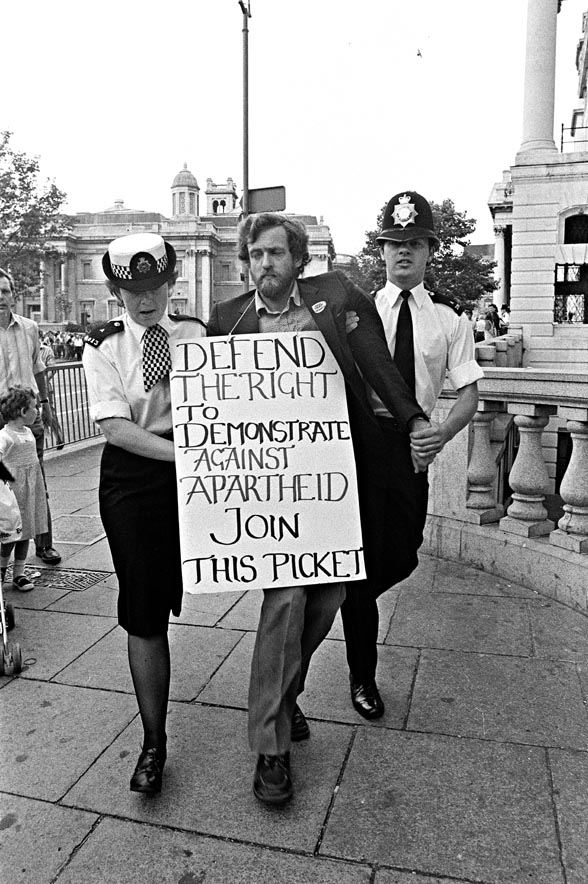

At approximately 6 p.m. a group of 18 demonstrators crossed the road and assembled in front of the Embassy. They began to sing, chant slogans, distribute leaflets and collect signatures. Within 5 or 6 minutes a massive police cordon surrounded the peaceful picketers. They were all arrested without being told why and bundled into waiting police vans.

Half an hour later, a further six protesters crossed the road and were also arrested. The twenty-four anti-apartheid demonstrators were taken to Albany Street police station. They were all released without charge, after only a couple of hours, but not before one black picketer was accused of being an illegal immigrant and threatened with indefinite detention. She too was released without charge, less than an hour after the others.

In response to this ban on demonstrations, City Group convened the South African Embassy Picket Campaign (SAEPC) to win back the right to protest against apartheid directly in front of the South Africa House. The defiance of the ban continued, with people risking arrest each Friday. On 15 June, Commander Howlett met with Mike Terry from the national Anti-Apartheid Movement to discuss the ban. In a witness statement (dated 6 July), Commander Howlett described this meeting in the following terms:

In response to this ban on demonstrations, City Group convened the South African Embassy Picket Campaign (SAEPC) to win back the right to protest against apartheid directly in front of the South Africa House. The defiance of the ban continued, with people risking arrest each Friday. On 15 June, Commander Howlett met with Mike Terry from the national Anti-Apartheid Movement to discuss the ban. In a witness statement (dated 6 July), Commander Howlett described this meeting in the following terms:

On Friday, 15th June 1984, at 10.15 am, together with Chief Superintendent Richards and Inspector Menear, I met, at my request, in my office, Mr Mike Terry and Miss Cate Clark of the Anti-Apartheid Movement. I explained the change in police policy and the reasons for it to them. A note of the meeting has been kept by the police. Mr Terry expressed their opposition to the change and indicated that steps to alter that policy would be taken and that his organisation intended that those steps be legal as his movement did not seek confrontation.

When a representative of the SAEPC met with the police later that day, they were advised to follow the lead of the AAM in avoiding confrontation. The SAEPC did not take that advice – that evening, twenty-six protesters crossed Duncannon Street to break the ban. This time, they were charged with obstructing the police in the cause of their duties (in this context, their duties were said to be protecting the ‘peace and dignity‘ of the South African Embassy in line with the Vienna Convention).

On Friday 22 June, David Kitson (who had, by then, been released from jail in South Africa) watched twenty-two anti-apartheid activists, including his son Steve, be arrested for defying the ban. As the defendants began appearing at Bow Street Magistrates Court the following week, strict bail conditions were imposed, preventing the defendants from standing on Morley’s Hill, the pavement in front of South Africa House. By 16 July, 137 people had been arrested as a result of the South African Embassy Picket Campaign and five had been imprisoned for breach of the bail conditions forbidding them from demonstrating within 30 yards of the embassy. During the course of a 24-hour protest on 21/22 July 1984, five councillors and three MPs – Tony Banks, Stuart Holland, and Jeremy Corbyn were arrested for breaking the ban.

In act of solidarity with its arrested councillors and the SAEPC, Camden Council took a legal opinion, on the legality of the ban, from Stephen Sedley QC. His view was that,

The Vienna Convention 1961, insofar as it is incorporated in the Diplomatic Privileges Act 1964, adds nothing to the duties, nor therefore to the powers, of the police in this regard. It follows, if I am right, that their action in declining to allow continuance of the demonstrations on the pavement outside South Africa House was an abuse of their powers, and that they were not executing any duty known to the law when they cleared the pavement and arrested persons who remained there.

One of the City Group defendants, Richard Roques, agreed to stand as a test case. On 1 August 1984, at Bow Street Magistrates Court, the Chief Stipendiary Magistrate for Central London, Mr Hopkins, dismissed the charges against Richard. A week later, in light of this decision, the police dropped the charges against the other 136 protesters who had been arrested during the campaign (including the five who had been imprisoned). The victory for the SAEPC was an embarrassment for the national Anti-Apartheid Movement. The Executive Committee of the AAM issued a statement on 10 July 1984 (the day four of the defendants were first threatened with imprisonment, if they breached their bail conditions). Their statement outlined a series of meetings they had arranged with senior police officers to try to negotiate an end to the ban:

It is the view of the Executive that until the above process has been exhausted and the EC has met to further assess the situation, the AAM and its local groups should not demonstrate immediately in front of South Africa House.

The AAM has been approached by a number of local groups and others seeking advice on the ‘”South African Embassy Picket Campaign 1984″. The AAM EC does not support their approach, believes that it damages the prospect of achieving a removal of the ban, and therefore asks its members and supporters not to participate in this campaign.

The AAM were wrong to be so cautious. Although City Group and the SAEPC won back the right to protest outside the South African Embassy through their civil disobedience, their victory would come at a cost. City Group’s defiance of the AAM EC’s guidance accelerated the deterioration of the (already strained) relationship between the national movement and its ‘hooligan element’ in the City of London. The conduct of the SAEPC remained a contentious issue with the AAM and directly contributed to City Group’s ‘disaffiliation‘ from the national movement the following year. City Group remained committed to taking direct action against apartheid, and civil disobedience to defend the right to protest. When the Metropolitan Police attempted the ban the Non-Stop Picket from outside the South African Embassy in May 1987, City Group was once again successful in defending their protest through direct action.

Pingback: Working with anti-apartheid memories | Non-Stop Against Apartheid

Apologies, I accidentally added this comment to this page. He has been credited here. Thank you so much for crediting him.

Anna

Hi Anna,

I know lots of people have been sharing this photi without crediting Rob, but we have paid him to use it on this site and whenever I see it appear on social media I have been adding comments to ensure your dad is credited.

Pingback: Viva Carol, our convenor. No one tougher, no one meaner | Non-Stop Against Apartheid

Pingback: Police Abolitionists Aren’t ‘Too Radical’ – They’ve Been Making Gains for Decades – LeftInsider